Inspired by SF Signal's recent Mind Meld posts on the "best genre-related books/films/shows consumed in 2009," I thought I might give my Top 10 lists for SF&F novels and short stories read this year (for the first time) -- seeing as most of what I read was originally published before 2009. Then, I'll throw in a list for films.

Favourite SF&F Novels Read in 2009 (Out of 4 Stars)

1. Watchmen (Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, 1986) *****

2. Red Mars (Kim Stanley Robinson, 1992) ****

3. Blindsight (Peter Watts, 2006) ****

4. Anathem (Neal Stephenson, 2008) ****

5. Green Mars (Kim Stanley Robinson, 1994) ****

6. River of Gods (Ian McDonald, 2004) ****

7. Revelation Space (Alastair Reynolds, 2000) *** 1/2

8. The Last Unicorn (Peter S. Beagle, 1968) *** 1/2

9. Chasm City (Alastair Reynolds, 2001) ***

10. Darwin's Radio (Greg Bear, 1999) ***

Most Disappointing: Calculating God (Robert J. Sawyer, 2000); Hominids (Robert J. Sawyer, 2003); Consider Phlebas (Iain M. Banks, 1987).

27 December 2009

25 December 2009

Further Thoughts on Avatar (dir. James Cameron, 2009)

Some further reviews and commentaries on Avatar:

• Nick Mamatas (a silly rant, interesting for the level and bile of its silliness)

• 'Avatar' and the War of Genres (Gerry Canavan)

• When Will White People Stop Making Movies Like "Avatar"? (Annalee Newitz @ io9)

• The Blue Future of Video Games (Stephen Totilo @ Kotaku)

• Intentions be damned, Avatar is racist (SEK @ Acephalous)

• John Scalzi on the most memorable SF films of 2009

• The Wertzone

• SF Signal (Scott Shaffer)

• Locus (Gary Westfahl)

• Speculative Horizons

I wrote in my other post on Avatar that Art functions to challenge and potentially change how we see our world and ourselves, relating this idea to what I think constitutes the central theme of the film: to see differently, to perceive in a new way.

One clear sign that a work of Art has succeeded in this function can be found in the multiplicity of readings, arguments, critiques, reactions, and emotions generated by the film. With Avatar, the variety and even vehemence of readings of the film are proving most important in this respect. If anything, the film is at least inspiring discussion and debate -- not just about whether it's awesome or sucks, but for its politics and sociocultural meanings.

More specifically, I suggest that a significant part of the film's success resides in its openness to multiple, various interpretations . . . as well as in the way it exposes, or reflects back, the reductiveness or overdetermination or oversimplification of some of those interpretations. Put in a slightly different way, Avatar, I think, is quickly becoming an excellent example of how people will see in a work of Art what they want, need, desire to see, thereby closing themselves off from, blinding themselves to, or outright distrusting the wider, more universal meanings at play in the film. In other words, Avatar appears to be generating both insightful commentary and misprisions (i.e., willfull misreadings).

A common critique of Avatar claims that the story is clichéd, conventional, too simple, unoriginal, boring, vapid, and so on. The standard question goes, "With all the investment in technology and making the film look great, why couldn't Cameron develop a better, more intelligent story?" By extension, the critique of the story involves charges that the script is poor, the dialogue being awkward and overly obvious and "cringe worthy."

On one hand, such a critique assumes (and discounts) that Cameron did not make careful, purposeful choices regarding the plot, characters, setting, and key incidents; on the other hand, such a critique also reveals an inattentiveness to the role of the dialogue in the film, which is to establish and forward plot, character, setting, and incident.

• Nick Mamatas (a silly rant, interesting for the level and bile of its silliness)

• 'Avatar' and the War of Genres (Gerry Canavan)

• When Will White People Stop Making Movies Like "Avatar"? (Annalee Newitz @ io9)

• The Blue Future of Video Games (Stephen Totilo @ Kotaku)

• Intentions be damned, Avatar is racist (SEK @ Acephalous)

• John Scalzi on the most memorable SF films of 2009

• The Wertzone

• SF Signal (Scott Shaffer)

• Locus (Gary Westfahl)

• Speculative Horizons

I wrote in my other post on Avatar that Art functions to challenge and potentially change how we see our world and ourselves, relating this idea to what I think constitutes the central theme of the film: to see differently, to perceive in a new way.

One clear sign that a work of Art has succeeded in this function can be found in the multiplicity of readings, arguments, critiques, reactions, and emotions generated by the film. With Avatar, the variety and even vehemence of readings of the film are proving most important in this respect. If anything, the film is at least inspiring discussion and debate -- not just about whether it's awesome or sucks, but for its politics and sociocultural meanings.

More specifically, I suggest that a significant part of the film's success resides in its openness to multiple, various interpretations . . . as well as in the way it exposes, or reflects back, the reductiveness or overdetermination or oversimplification of some of those interpretations. Put in a slightly different way, Avatar, I think, is quickly becoming an excellent example of how people will see in a work of Art what they want, need, desire to see, thereby closing themselves off from, blinding themselves to, or outright distrusting the wider, more universal meanings at play in the film. In other words, Avatar appears to be generating both insightful commentary and misprisions (i.e., willfull misreadings).

A common critique of Avatar claims that the story is clichéd, conventional, too simple, unoriginal, boring, vapid, and so on. The standard question goes, "With all the investment in technology and making the film look great, why couldn't Cameron develop a better, more intelligent story?" By extension, the critique of the story involves charges that the script is poor, the dialogue being awkward and overly obvious and "cringe worthy."

On one hand, such a critique assumes (and discounts) that Cameron did not make careful, purposeful choices regarding the plot, characters, setting, and key incidents; on the other hand, such a critique also reveals an inattentiveness to the role of the dialogue in the film, which is to establish and forward plot, character, setting, and incident.

Labels:

Avatar,

film,

James Cameron,

science fiction

20 December 2009

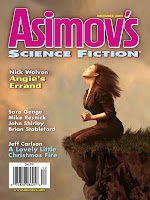

Reading Asimov's Science Fiction (Dec. 2009), Part V

[Part I; Part II; Part III; Part IV]

7. Mike Resnick, "The Bride of Frankenstein" (pg. 80-87) ***

Read 20 Dec. 2009. I think of this kind of story as a stunt. Not an experiment, but a stunt: like trying to see if you can jump through a burning ring of fire on a motorcycle while, maybe, juggling chainsaws. Mind you, the story is not that absurd, but it's a stunt nonetheless -- one that I enjoyed a great deal, particularly for its cheeky re-imagining of Mary Shelley's characters in a mostly-tidy domestic arrangement, with the creature as a dedicated pacifist who devours tragic romances such as Anna Karenina and Romeo and Juliet. The wife is our narrator, through entries in her journal, and we learn about her daily frustration with the loneliness and strangeness of her domestic life, not to mention her open distaste for Igor, the hunchbacked servant, and her manifest discomfort with the creature. One key is Resnick's revision of the creature: "'I don't kill things. . . . I have been dead, Baroness . . .. It is not an experience I would wish upon anyone or anything else'" (83); "'Therefore, we must be here for a higher purpose -- and what higher purpose can there be than love?'" (86). The other key is the tone of the narrative, which remains steadfastly light, in the sort of knowing, wink-wink, self-conscious lightness that understands the story is playing around with very familiar expectations while ending up basically at the same place as the original, yet shifting the register of the original (i.e., the creature's demand that Victor make him a mate) from tragedy to romance. I like Resnick's inventiveness, perhaps especially because I am so familiar with Mary Shelley's novel: (re)telling the story from the Baroness' point of view nicely resets our impressions of the dynamics between the characters. Yet I can't shake the feeling that the story's a stunt, that it might have done more with a "what if?" revision of that novel's story.

7. Mike Resnick, "The Bride of Frankenstein" (pg. 80-87) ***

Read 20 Dec. 2009. I think of this kind of story as a stunt. Not an experiment, but a stunt: like trying to see if you can jump through a burning ring of fire on a motorcycle while, maybe, juggling chainsaws. Mind you, the story is not that absurd, but it's a stunt nonetheless -- one that I enjoyed a great deal, particularly for its cheeky re-imagining of Mary Shelley's characters in a mostly-tidy domestic arrangement, with the creature as a dedicated pacifist who devours tragic romances such as Anna Karenina and Romeo and Juliet. The wife is our narrator, through entries in her journal, and we learn about her daily frustration with the loneliness and strangeness of her domestic life, not to mention her open distaste for Igor, the hunchbacked servant, and her manifest discomfort with the creature. One key is Resnick's revision of the creature: "'I don't kill things. . . . I have been dead, Baroness . . .. It is not an experience I would wish upon anyone or anything else'" (83); "'Therefore, we must be here for a higher purpose -- and what higher purpose can there be than love?'" (86). The other key is the tone of the narrative, which remains steadfastly light, in the sort of knowing, wink-wink, self-conscious lightness that understands the story is playing around with very familiar expectations while ending up basically at the same place as the original, yet shifting the register of the original (i.e., the creature's demand that Victor make him a mate) from tragedy to romance. I like Resnick's inventiveness, perhaps especially because I am so familiar with Mary Shelley's novel: (re)telling the story from the Baroness' point of view nicely resets our impressions of the dynamics between the characters. Yet I can't shake the feeling that the story's a stunt, that it might have done more with a "what if?" revision of that novel's story.

19 December 2009

Thoughts on Avatar (dir. James Cameron, 2009)

Beauty is truth, truth beauty, -- that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

– John Keats, "Ode on a Grecian Urn"

True Wit is Nature to Advantage drest,

What oft was Thought, but ne'er so well Exprest,

Something, whose Truth convinc'd at Sight we find,

That gives us back the Image of our Mind ....

– Alexander Pope, An Essay on Criticism

Something, whose Truth convinc'd at Sight we find,

That gives us back the Image of our Mind ....

– Alexander Pope, An Essay on Criticism

One of the basic functions of Art is to challenge us to see our world and ourselves in new ways, to perceive and look at Life differently.

To see in new ways, to perceive differently: this, we might say, is the raison d'être of science fiction, a genre/mode/tradition that relies upon the estranging and unfamiliar as a means by which to comment upon now, upon today.

Of all modern art forms, film most powerfully and concretely has the ability to change how we see our world and ourselves, to put before us the estranging and unfamiliar, thereby introducing us to new worlds whether they be of the past or the present or the future, another country or culture, other lives outside of or unknown to us.

Avatar does all of this, as a work of Art, of science fiction, of film -- on an epic, sublime, and breathtaking scale.

It seeks nothing less than to remind us of the stunning, heartbreaking beauty of Earth, a beauty that we must value as more than a mere commodity. It aims unabashedly to alter how we see Earth by giving us Pandora, a world so magnificently surprising and colourful and alive that it asks us to be swept away by and utterly immersed in the beauty of its newness . . . asks us to care for it and protect it from ourselves.

Labels:

Avatar,

film,

James Cameron,

science fiction

Reading Asimov's Science Fiction (Dec. 2009), Part IV

Read 17 Dec. 2009. Smart, humourous, witty, focussed, sly. Hints of homage to Douglas Adams. A climax and an ending that neatly balance the expected and the slightly ambiguous. This is a fine, fine story, starting with the title and not slowing down until the last word; I wonder if it will appear in some "Best of 2009" collections next year. One thing that Crowell does especially well is maintain what I'll call a consistency of tone, of voice: the writing has energy, confidence, purpose, intelligence, keeping the narration neatly poised between Horatian satire and a kind of honest, wry appraisal of why humanity has all the necessary skills to forge a unity among various alien peoples in spite of itself. Sidibé's simple desire to help a fellow diplomat on board the "GalCiv" spaceship leads her, innocently, to form an intricate network of trading goods and favours, which leads to the importance of the bucket -- not to mention some of the aliens in her "cohort" aboard the spaceship suspecting that she's ultimately after "Complete galactic domination" (74). In the end, this is what she achieves, just not quite in the way we (or she) would expect, for in just going about the daily business of the trade network and wishing for a 15-minute nap between appointments, she cultivates co-operation among all her fellow GalCiv diplomats. "'I was only -- you can't -- I don't really know what I'm doing. They didn't vote for me or anything'" (79): her reward? Why, the godlike mastery of spacetime, of course, bestowed by, well ... perhaps by God himself/herself/itself. In the end, the story is positive, optimistic: humanity as the connector of the Milky Way's races and nations, despite its intentions to the contrary. Sly, indeed.

7. Mike Resnick, "The Bride of Frankenstein"

8. Brian Stableford, "Some Like it Hot"

16 December 2009

Reading Asimov's Science Fiction (Dec. 2009), Part III

Read 16 Dec. 2009. A very strong story, from the craft of the words to the strength and complexity of the main character Angie to the plotting and resolution. This is the sort of quality writing I expect to find in a top market such as Asimov's. Wolven presents a distinct voice in the narrator and demonstrates an attentive ear for sound and rhythm: "The sheer waste of it made her stomach knot, but afterward her blonde hair fell in feathery masses that softened the severity of her starved cheeks" (45); "Vestiges of glass in the frames of townhouse windows glistened in the afternoon light like unshed tears" (50). There's crispness in the language, and poetry. Angie encourages the reader's sympathy: the older sister turned single mother to her sisters and brother after the "Crisis" (a deliberately vague recent apocalyptic event); she is at a point of crisis herself, believing she needs a man for help and support; she faces a nearly predictable danger because of this belief, and comes through changed with an inner conviction, "patience," and "confidence" (54) -- a change that develops plausibly, naturally from the story's incidents. Those incidents are measured carefully, generating and never quite fully releasing a tension that infuses everything in the story (characters, setting, events, words). On the cusp of giving in to the cliché consequences of a lone, vulnerable woman in a threatening world of lawless men, Wolven throws a couple of twists at the reader that bring relief but also pathos. This story treats gender roles and stereotypes in a more neutral, thoughtful way than Genge, as people revert to old, primal needs yet also find new sources of strength because of the "Crisis." A few moments of awkwardness set the story back a tad, though ("At the word spoil a sob rose in her throat. She swallowed it hastily, releasing Emily's collar" [44]).

15 December 2009

Reading Asimov's Science Fiction (Dec. 2009), Part II

[Part I.]

2. Sara Genge, "As Women Fight" (pg. 24-33) **

2. Sara Genge, "As Women Fight" (pg. 24-33) **

Read 13 Dec. 2009. This story has an inventive idea, and metaphor, at its centre: a somewhat evolved human culture, apparently owing to the influence of long-ago visitors from outer space, is built around the potentially annual exchange of bodies between husbands and wives -- rather, exchange of personalities, or selves -- depending on who wins a "Fight" (actual, ritualized physical combat). Yet the story is too heavy-handed with its biases regarding the implications of this idea/metaphor. People switch bodies in order to inhabit, experience, and understand the minds and desires and proscribed roles of both genders; the women, however, are made to be the more desirable choice (faster, heightened senses, etc.) overall, while the men fit into clichéd behaviours and types, despite the story's admirable attempts to blur and challenge gender constructions/constrictions. The main character, Merthe, is an effective focalizer: ambiguous; confused; at a point of personal and cultural conflict, and so willing to do things differently and accept the consequences; chivalrous, heroic. I wonder, though, if switching bodies and a transferrable consciousness/self/personality aren't becoming overly conventional in SF now? Also, Genge seems to be reaching for the substance of Russ or Tiptree, Jr., but the . . . artistry feels not quite up to the task.

11 December 2009

Reading Asimov's Science Fiction (Dec. 2009)

Certainly, if planning to write stories and get them published, reading and knowing the best markets is a good thing. Hence, I will make an effort to read issues of Asimov's consistently for a few months and try to gauge the kind of story that gets sold to and finds its way into this leading market.

I will give each story a rating (out of four stars) and offer my thoughts on what did and/or did not work.

1. Jeff Carlson, "A Lovely Little Christmas Fire" (pg. 10-22) ** 1/2

Read 12 Dec. 2009. This is a good, serviceable story with a dash of humour and a sprinkle of hardboiled-detective attitude. The point of view of the main character, Julie Beauchain, feels a bit artificial at times: the narrative is too pointed in ensuring that the reader knows she's black and a woman and hot for her man/partner Highsong. Yet the bringing together of current corporate capitalist greed and US defense/military R&D initiatives in genetically engineered and augmented termites allowed to run amok makes for an intriguingly plausible dystopian America. Tightly paced and plotted; entertaining; engaging main character. For me, though, it ultimately lacks a multilayered substance in its meaning(s), and the writing at times is awkward or a little forced (e.g., "If she was worth her weight, she would've jumped Highsong or at least smooched a bit ..." [p. 18]).

2. Sarah Genge, "As Women Fight"

3. John Shirley, "Animus Rights"

I will give each story a rating (out of four stars) and offer my thoughts on what did and/or did not work.

1. Jeff Carlson, "A Lovely Little Christmas Fire" (pg. 10-22) ** 1/2

Read 12 Dec. 2009. This is a good, serviceable story with a dash of humour and a sprinkle of hardboiled-detective attitude. The point of view of the main character, Julie Beauchain, feels a bit artificial at times: the narrative is too pointed in ensuring that the reader knows she's black and a woman and hot for her man/partner Highsong. Yet the bringing together of current corporate capitalist greed and US defense/military R&D initiatives in genetically engineered and augmented termites allowed to run amok makes for an intriguingly plausible dystopian America. Tightly paced and plotted; entertaining; engaging main character. For me, though, it ultimately lacks a multilayered substance in its meaning(s), and the writing at times is awkward or a little forced (e.g., "If she was worth her weight, she would've jumped Highsong or at least smooched a bit ..." [p. 18]).

2. Sarah Genge, "As Women Fight"

3. John Shirley, "Animus Rights"

4. Nick Wolven, "Angie's Errand"

5. Jim Aikin, "Leaving the Station"

6. Benjamin Crowell, "A Large Bucket, and Accidental Godlike Mastery of Spacetime"

7. Mike Resnick, "The Bride of Frankenstein"

8. Brian Stableford, "Some Like it Hot"

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)