[WARNING: POTENTIAL SPOILERS]

Three days ago, I finished Kim Stanley Robinson's Blue Mars (1996), the final novel in his Mars trilogy. I took nearly a year to read all three books, with breaks -- for various reasons -- between the first two, Red Mars (1993) and Green Mars (1994). For me, the Mars trilogy stands not just as one of the true masterworks of 20th-century SF, but also as one of the great achievements in 20th-century fiction regardless of genre.

What follows is not a coherent argument about why I hold such a high opinion of the trilogy, but more a collection of thoughts on the books that should comprise a fairly decent picture of that opinion.

• Three Books As One. The trilogy needs to be seen as a single whole, not unlike The Lord of the Rings. It's not just the consistency of the same core characters in the three books, or the central themes that run through and evolve during the series (colonialism, science and/as politics, memory and nostalgia, the powers and perils of human ingenuity, self-interests vs. community interests, debates about terraforming and economic systems, etc.), or the progress of about 200 years of internal and alternate history that tangibly affects the characters' lives. As a single whole, the trilogy maintains a persistent, unifying vision and tone, a particular feel or atmosphere -- centred in Robinson's evocation of the landscape, colours, conditions, challenges, and alienness of Mars.

Also, simply, the trilogy constitutes one long story/narrative, and a story/narrative that closes its circle(s) by returning to its beginning at its end, in an act of narrative nostalgia, reader nostalgia, and character nostalgia, with all three elements changed in the journey from beginning to end and reminded of that change. By the close of Blue Mars, the weight of everything experienced by the characters and the reader since Red Mars feels immense, complex, intimate, organic, inspiring, sublime. Humanity has such potential for beauty and wonder . . . it need only overcome itself.

• Walkabout. Around halfway into Green Mars, I began thinking of the trilogy as a distinctly "ambulatory" narrative. Characters constantly move about Mars: John Boone's solo navigation of the new world and its burgeoning cultures, or Nadia and Arkady's flight around the planet, in Red Mars; Nirgal seeing the world for the first time with Coyote in Green Mars; Ann and Sax, separately, exploring the untouched or increasingly alive parts of the planet in Blue Mars. There are many more examples, and together they all constitute a sort of baseline plot structure for the trilogy (at micro- and macro-levels). Robinson unfolds Mars to readers by repeatedly taking them on treks and trips and travels over the planet's entirety, above and below ground, in the air and on the seas, even occasionally into orbit. Most importantly, though, he does this through the individual viewpoints of a variety of characters who see and approach Mars with their own motivations, needs, uncertainties, hopes. So, Mars remains perpetually new and surprising; it keeps changing, physically and socioculturally.

Doing this also lets Robinson create and develop what I call the "poetry" of Mars. Whether it's John Boone marvelling at the planet's craters and chasms and chaoses (Red Mars), or Sax and Maya picking out and naming the different colours of Martian sunsets (Blue Mars), Mars becomes an utterly fascinating and plausible and concretely detailed alien landscape -- with a beauty all its own, at local and individual as well as global and communal scales. So much of the vision and tone of the trilogy reside in this "poetry" of Mars, whether Robinson spends time carefully detailing the biological/chemical make-up of Martian rock and dirt or the procedures for altering Mars' atmosphere to make the surface breathable. This is how Mars acquires substance, substantiality. This is how Robinson provides opportunities for the reader to become invested in the world, the characters, the story.

12 July 2010

15 June 2010

I Hype, You Hype, We All Hype

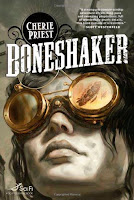

My previous post on Cherie Priest's Boneshaker, hype, and taste has sparked a bit of discussion in other online places, and I thought I would add some further thoughts related to what I read in those places.

First of all, author Mark Charan Newton, in his post Good Hype, Bad Hype, offers some valuable insight on the role of hype in the book trade. Good hype, he writes, is the traditional "word-of-mouth" talk about a book, "decentralised" and of "the people" -- which now occurs in "internet forums and blogs"; this sort of hype is good "because it causes discussion, gets people excited and ... is not influenced by corporations." Bad hype, on the other hand, involves a process beginning, essentially, with publishers/publicists and the "marketing blurbs" they use to "get reviewers excited" about and so "raise expectations" for a book, which they hope are passed on to readers; this is hype as seduction, as "marketing speak," and must be distrusted. Newton concludes with the observation that, from an author's point of view, "it's better to be talked about than not talked about" (alluding to one of the fine witticisms of the estimable Oscar Wilde).

The corollary to Newton's conclusion, I suppose, is that all press is good press, particularly if such "press" keeps an author and his or her books on people's shelves and in people's conversations. In a highly competitive marketplace such as publishing, and more specifically such as the SF&F field, being part of the conversation is certainly crucial, and authors have an array of tools now to do so. My concern in my original post on Boneshaker, though, related to how the conversation about the novel -- to use Newton's distinctions -- predominantly assumed the tone of seductive "marketing speak," misleadingly raising expectations for it. Thus, there can be bad hype masquerading as good hype, influencing readers' tastes and potentially straying from more honestly critical assessments of books (whether positive, negative, or neutral).

Gav's post on NextRead, Comment: When a good book is just a good book..., makes for a fitting companion piece to Newton's post, as he spends some time delving into the matter of hype from the perspective of the reviewer. He acknowledges that publishers want to "sell" a book as "the best thing since xyz" and considers how reviewers might or should handle these situations, where a publisher's hype may find its way into the "hyperbole" of a review. He suggests, "Bloggers though should probably ... take care that they are actually saying something of substance." Furthermore, he wonders whether reviewing can sometimes involve a "nervousness to be more direct" about a book's flaws, which entails the risk of steering readers away from "a book that we on the whole liked." At the end of his post, Gav closes with a rather self-reflective promise: "For my own part I'm going to try and be more sensitive [to] hyperbole and try my best to keep calling a spade a spade." Thus, he identifies a way in which reviewing can manage expectations for a book, perhaps better serving readers through more honest appraisals.

Such honest appraisals are important, otherwise the "wrong impression" is communicated, potentially leading readers to believe a book is "the next blockbuster" that could "change your life." In this context, Gav quotes from my original post as an example of what happens when reviews create the "wrong impression," which certainly occurred in my case. I never expected Boneshaker to change my life (I leave that to the bonafide classics, inside and outside of SF&F), but I did expect what a great number of reviewers claimed I would get in the novel: fun, entertainment; fast-paced action; something new and fresh. Reviewers, I discovered, had not called a spade a spade. Hence, I became interested in thinking about the consequences of hype as seen specifically with online reviews.

First of all, author Mark Charan Newton, in his post Good Hype, Bad Hype, offers some valuable insight on the role of hype in the book trade. Good hype, he writes, is the traditional "word-of-mouth" talk about a book, "decentralised" and of "the people" -- which now occurs in "internet forums and blogs"; this sort of hype is good "because it causes discussion, gets people excited and ... is not influenced by corporations." Bad hype, on the other hand, involves a process beginning, essentially, with publishers/publicists and the "marketing blurbs" they use to "get reviewers excited" about and so "raise expectations" for a book, which they hope are passed on to readers; this is hype as seduction, as "marketing speak," and must be distrusted. Newton concludes with the observation that, from an author's point of view, "it's better to be talked about than not talked about" (alluding to one of the fine witticisms of the estimable Oscar Wilde).

The corollary to Newton's conclusion, I suppose, is that all press is good press, particularly if such "press" keeps an author and his or her books on people's shelves and in people's conversations. In a highly competitive marketplace such as publishing, and more specifically such as the SF&F field, being part of the conversation is certainly crucial, and authors have an array of tools now to do so. My concern in my original post on Boneshaker, though, related to how the conversation about the novel -- to use Newton's distinctions -- predominantly assumed the tone of seductive "marketing speak," misleadingly raising expectations for it. Thus, there can be bad hype masquerading as good hype, influencing readers' tastes and potentially straying from more honestly critical assessments of books (whether positive, negative, or neutral).

Gav's post on NextRead, Comment: When a good book is just a good book..., makes for a fitting companion piece to Newton's post, as he spends some time delving into the matter of hype from the perspective of the reviewer. He acknowledges that publishers want to "sell" a book as "the best thing since xyz" and considers how reviewers might or should handle these situations, where a publisher's hype may find its way into the "hyperbole" of a review. He suggests, "Bloggers though should probably ... take care that they are actually saying something of substance." Furthermore, he wonders whether reviewing can sometimes involve a "nervousness to be more direct" about a book's flaws, which entails the risk of steering readers away from "a book that we on the whole liked." At the end of his post, Gav closes with a rather self-reflective promise: "For my own part I'm going to try and be more sensitive [to] hyperbole and try my best to keep calling a spade a spade." Thus, he identifies a way in which reviewing can manage expectations for a book, perhaps better serving readers through more honest appraisals.

Such honest appraisals are important, otherwise the "wrong impression" is communicated, potentially leading readers to believe a book is "the next blockbuster" that could "change your life." In this context, Gav quotes from my original post as an example of what happens when reviews create the "wrong impression," which certainly occurred in my case. I never expected Boneshaker to change my life (I leave that to the bonafide classics, inside and outside of SF&F), but I did expect what a great number of reviewers claimed I would get in the novel: fun, entertainment; fast-paced action; something new and fresh. Reviewers, I discovered, had not called a spade a spade. Hence, I became interested in thinking about the consequences of hype as seen specifically with online reviews.

Labels:

Boneshaker,

Cherie Priest,

essay,

science fiction

11 June 2010

Cherie Priest's Boneshaker, Hype, and Taste

[WARNING: POSSIBLE SPOILERS.]

Guy Gavriel Kay, in his June 4th guest blog for BSC on "Under Heaven, and the Book World Under Siege," discusses how the internet has fundamentally changed the relationship between authors and their works, between authors and their readers. "The principle consequence," he writes, "is the disappearance of spaces ... between author and consumer and between author and work." One such space is that of privacy: authors increasingly lack this privacy, Kay observes, as readers/consumers believe they have a "connection" with a "writer online" and so can feel justified in attacking an author for, say, being late with a new novel; yet authors participate in this wearing away of their privacy by blogging about their daily lives, by needing to maintain an online presence in order to market their works and their personality (or, brand). From Kay's perspective, this lack of privacy for authors risks "eroding . . . the space that can be necessary to produce not only good art but a good life." Certainly, Kay reveals a nostalgia for a perhaps simpler time when authors truly enjoyed a kind of distance from readers. Yet, from the perspective of a reader, I see a further implication of the internet's effect upon Kay's "spaces." Namely, we are potentially also witnessing a lessening of the distinction between the critic and the general reader, with the consequence that authors and their works can quickly receive a great deal of hype -- often at the expense of more critical assessments of those works, of more considered reflection upon the grounds of taste.

My experience with Cherie Priest's Boneshaker (Tor, 2009) led me to thinking about these issues.

Guy Gavriel Kay, in his June 4th guest blog for BSC on "Under Heaven, and the Book World Under Siege," discusses how the internet has fundamentally changed the relationship between authors and their works, between authors and their readers. "The principle consequence," he writes, "is the disappearance of spaces ... between author and consumer and between author and work." One such space is that of privacy: authors increasingly lack this privacy, Kay observes, as readers/consumers believe they have a "connection" with a "writer online" and so can feel justified in attacking an author for, say, being late with a new novel; yet authors participate in this wearing away of their privacy by blogging about their daily lives, by needing to maintain an online presence in order to market their works and their personality (or, brand). From Kay's perspective, this lack of privacy for authors risks "eroding . . . the space that can be necessary to produce not only good art but a good life." Certainly, Kay reveals a nostalgia for a perhaps simpler time when authors truly enjoyed a kind of distance from readers. Yet, from the perspective of a reader, I see a further implication of the internet's effect upon Kay's "spaces." Namely, we are potentially also witnessing a lessening of the distinction between the critic and the general reader, with the consequence that authors and their works can quickly receive a great deal of hype -- often at the expense of more critical assessments of those works, of more considered reflection upon the grounds of taste.

My experience with Cherie Priest's Boneshaker (Tor, 2009) led me to thinking about these issues.

Labels:

Boneshaker,

Cherie Priest,

essay,

science fiction

02 March 2010

Saving Science Fiction From Itself?

Kristine Kathryn Rusch's essay "Barbarian Confessions," from the book Star Wars on Trial: Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Debate the Most Popular Science Fiction Films of All Time (eds. David Brin and Matthew Woodring Stover, 2006), is currently available on the Smart Pop Books web site, but only for a limited time (until March 5th, apparently). I was originally linked to it from SF Signal.

John DeNardo of SF Signal terms Rusch's essay "controversial," which certainly encouraged me to read it. The controversy, I suspect, stems from Rusch's diagnosis of the condition of SF and her recommendations for how the genre can heal and remain healthy.

The basic aim of this diagnosis involves a defense of tie-in novel series (i.e., for Star Trek or Star Wars, and the like), which is the sort of SF generally looked down upon by what Rusch calls "the Science Fiction Village," yet also the sort of SF that sells well, takes up its share of "shelf space," and -- most importantly, for Rusch -- entertains its readers. (Rusch herself has written several tie-in novels.) SF, Rusch argues, has strayed from and actively resists what makes Star Wars great: "an escape, a journey into a new yet familiar world, entertainment. A good read." Such resistance to "entertainment" began with the New Wave, the result being the predominance of "dystopian universes," "nasty ... world-building," and "insularity," along with the abandonment of "gosh-wow, sense-of-wonder stories." Therefore, according to Rusch, the prescription for SF is "more grand adventure, more heroes on journeys, more uplifting ... endings": the very stories offered by tie-in novels, which Rusch claims are "keeping SF alive."

For me, Rusch's essay proves especially relevant with regard to James Cameron's film Avatar, particularly a strain of negative response to the film within the SF&F community. I wish to address this negative response to Avatar by comparing it to the consistently positive response to Duncan Jones' Moon, where Avatar represents SF-as-entertainment and Moon SF-as-"work" (Rusch's term). I am fascinated by and deeply appreciate both films for what they do as films and as SF. Yet, echoing Rusch, I believe Avatar will do more than Moon to keep SF alive as a thriving and relevant genre. In fact, Avatar is the kind of film (and possible novel tie-in) that can save SF from itself.

John DeNardo of SF Signal terms Rusch's essay "controversial," which certainly encouraged me to read it. The controversy, I suspect, stems from Rusch's diagnosis of the condition of SF and her recommendations for how the genre can heal and remain healthy.

The basic aim of this diagnosis involves a defense of tie-in novel series (i.e., for Star Trek or Star Wars, and the like), which is the sort of SF generally looked down upon by what Rusch calls "the Science Fiction Village," yet also the sort of SF that sells well, takes up its share of "shelf space," and -- most importantly, for Rusch -- entertains its readers. (Rusch herself has written several tie-in novels.) SF, Rusch argues, has strayed from and actively resists what makes Star Wars great: "an escape, a journey into a new yet familiar world, entertainment. A good read." Such resistance to "entertainment" began with the New Wave, the result being the predominance of "dystopian universes," "nasty ... world-building," and "insularity," along with the abandonment of "gosh-wow, sense-of-wonder stories." Therefore, according to Rusch, the prescription for SF is "more grand adventure, more heroes on journeys, more uplifting ... endings": the very stories offered by tie-in novels, which Rusch claims are "keeping SF alive."

For me, Rusch's essay proves especially relevant with regard to James Cameron's film Avatar, particularly a strain of negative response to the film within the SF&F community. I wish to address this negative response to Avatar by comparing it to the consistently positive response to Duncan Jones' Moon, where Avatar represents SF-as-entertainment and Moon SF-as-"work" (Rusch's term). I am fascinated by and deeply appreciate both films for what they do as films and as SF. Yet, echoing Rusch, I believe Avatar will do more than Moon to keep SF alive as a thriving and relevant genre. In fact, Avatar is the kind of film (and possible novel tie-in) that can save SF from itself.

Labels:

Avatar,

essay,

film,

Kristine Kathryn Rusch,

Moon,

science fiction

25 February 2010

Reading Asimov's Science Fiction (Jan. 2010), Part IV

• See Part I.

• See Part II.

• See Part III.

6. Carol Emswhiller, "Wilds" (pg. 76-82) *** 1/2

Read 2 Feb. 2010. This story is a strange one to find in Asimov's: not clearly either SF or fantasy. Yet it is wholly engrossing and superbly executed. I'm going to call it a fantasy of sorts (maybe even a fable), as its unnamed first-person narrator lives out the fantasy of escaping from and leaving behind the everyday world of rental cars, jobs, neighbours, and so forth, by discovering and then surviving in "the wilds" (77). The world rejected by the narrator is our world, now -- not an SF near-future or alternate past, but now. Emshwiller thus constructs a fantasy of the reconnection with nature and the primal and the physical, wholly unmediated by technology or other modern conveniences: a fantasy of awakening to one's deepest and true desires ("But even as I swallow little snakes, I'm singing" [77]), and so to one's essential self, the world be damned ("I look at my reflection and I see exactly who I am" [82]). For the narrator, such rejection and reconnection relies upon "hiding" as his "way of life" (77): finding the highest, most inaccessible place "away from everybody" (76); building a tower of stones to give himself a better view, but making it look like a "natural formation" (77); eventually, he dresses "in mud" and smells of "ferns" (82), invisible to campers and hikers. Even the woman who shows up at his mountain with a Gucci purse filled with $50,000 worth of $100 bills is escaping and hiding. She's running from the law, certainly, having "'just picked ... up'" (81) an unguarded bag containing the money, then buying herself the Gucci purse, dinner at a "'fancy French restaurant'" (81), and a car -- as she says, "'Stuff I've never had before'" (81). She acted in defiance, then, of a world that alienates her (economically, materially), a world to which she was hidden. However, her motives for coming to "the wilds" are not as pure as the narrator's, for she remains tied to the material(ist) desires of the world, wanting to retrieve the bills scattered about the narrator's mountain, instead of, like the narrator, truly confronting her self and becoming "part of the wilds" (79). All of this is told by Emshwiller with a sharply focussed and consistent voice, the narrator's short and constrained sentences feeling decisive and practical, offering only as much communication as is necessary, but everywhere hinting at loss and nostalgia. What sort of world, we might ask, causes a man to cast it off utterly, to the point of real nakedness and drinking water "as an animal would" (82)? What is so alienating about such a world that a man's true self is concealed from him. The narrator does something I suspect many of us have contemplated or fantasised about doing. Yet the cost of his victory suggests caution at the end, for he achieves a wholly solitary life, hidden from campers and hikers, secretively leaving $100 bills in their shoes and pockets and hats while they sleep, playing "mysterious" (82) songs on his flute at night. I am sympathetic to his desires and choices, even jealous of them. I don't know that I would have the courage to realise them.

06 February 2010

SF Signal Meme: What Book Are You Reading Now?

I haven't done something like this before, but thought I would follow the meme started by John DeNardo at SF Signal, What Book Are You Reading Now?

(1) What book are you reading now?

Redemption Ark, by Alastair Reynolds.

(2) Why did you choose it?

Last year, I read and loved Revelation Space and Chasm City, so I want to continue with and finish Reynolds' Revelation Space trilogy (Absolution Gap is on deck). As well, I am now a dedicated fan of Reynolds' work, so I want to see if I can get caught up with all his novels in the next, say, year or there about. Finally, after recently reading some Earth-based, near-future SF (Beggars in Spain, Snow Crash), I was in the mood for a far-future space opera.

(3) What's the best thing about it?

I'm just about 100 pages in, so obviously I can't speak to the novel as a whole, but Reynolds is doing in Redemption Ark what I enjoyed in Revelation Space: shifting between a variety of point-of-view characters, moving the reader not just among different perspectives but different parts of the setting (geographically, politically, historically) ... not to mention different subjective timelines. Though it's early chapters yet, I'm already curious about the relationships and tensions between the Conjoiners and Demarchists, because the characters are intriguing, distinct. Then there's Reynolds' always fascinating far-future tech and neo-cyberpunk sensibility.

(4) What's the worst thing about it?

Again, I'm only about 100 pages in, but I will say that some of the shifts between different point-of-view characters are not signalled clearly enough, especially when they occur within the same chapter. I've found myself disoriented a couple of times (but I found my way quickly enough). Also, I'm not sure why, but it's taken me at least three or four attempts to start and make significant progress into each Reynolds novel I've read. I wonder if it's about becoming accustomed to Reynolds' style or about the density of information Reynolds establishes right away? Or, both? In any case, once I really get going, putting down a Reynolds novel is not easy.

(1) What book are you reading now?

Redemption Ark, by Alastair Reynolds.

(2) Why did you choose it?

Last year, I read and loved Revelation Space and Chasm City, so I want to continue with and finish Reynolds' Revelation Space trilogy (Absolution Gap is on deck). As well, I am now a dedicated fan of Reynolds' work, so I want to see if I can get caught up with all his novels in the next, say, year or there about. Finally, after recently reading some Earth-based, near-future SF (Beggars in Spain, Snow Crash), I was in the mood for a far-future space opera.

(3) What's the best thing about it?

I'm just about 100 pages in, so obviously I can't speak to the novel as a whole, but Reynolds is doing in Redemption Ark what I enjoyed in Revelation Space: shifting between a variety of point-of-view characters, moving the reader not just among different perspectives but different parts of the setting (geographically, politically, historically) ... not to mention different subjective timelines. Though it's early chapters yet, I'm already curious about the relationships and tensions between the Conjoiners and Demarchists, because the characters are intriguing, distinct. Then there's Reynolds' always fascinating far-future tech and neo-cyberpunk sensibility.

(4) What's the worst thing about it?

Again, I'm only about 100 pages in, but I will say that some of the shifts between different point-of-view characters are not signalled clearly enough, especially when they occur within the same chapter. I've found myself disoriented a couple of times (but I found my way quickly enough). Also, I'm not sure why, but it's taken me at least three or four attempts to start and make significant progress into each Reynolds novel I've read. I wonder if it's about becoming accustomed to Reynolds' style or about the density of information Reynolds establishes right away? Or, both? In any case, once I really get going, putting down a Reynolds novel is not easy.

05 February 2010

Reading Asimov's Science Fiction (Jan. 2010), Part III

• See Part I.

4. Chris Roberson, "Wonder House" (pg. 53-69) *** 1/2

Read 31 Jan. 2010. Alternate history SF, (re)imagining the confluence of events and inspirations that created the comic book. I will admit that I thoroughly enjoy this sort of story, which meditates on not just the origins of a form/media (comics) but also treats with playful reverence the origins and concerns of its own genre (SF) -- and does succinctly, never swerving from its tone or its subject, moving the story (and the reader) inexorably to the moment of revelation that is a joy because it is understood, anticipated right at the last second before it arrives. On the planet "Fire Star" (54), Yacov Leiber and Itzhak Blumenfeld have been running "Wonder House Publications" (53) for twenty years, their fortunes rising adn falling (or plateauing) by their ability to publish "terribles" (54) -- i.e., pulp magazines -- that readers desire. Roberson brings us into their publishing house and lives at a moment of crisis and the need for change, as Wonder House's fortunes are in decline, Yacov and Itzhak's editing a bit out of step with readers' current tastes. They brainstorm different ideas for new or renewed stories and series, such as "'war title'" (55) or a "'gun-slinger title'" (55) or a "'character title, like Doctor Buckingham'" (55) or "relaunching Celestial Bureaucracy'" (56), but find various reasons why such titles would not work in the present climate for terribles. In the process, Roberson crafts a history of Fire Star's terribles, which clearly mirrors Earth's history of the the pulps (especially from the Gernsback era of the late 1920s on, I think), bringing that history to a point of transition, for what Wonder House needs is something truly new, truly innovative if it will reclaim its "readership" (57) and marketshare. That something truly new is the simultaneous arrival of SF and comics, as Segal, a young writer doggedly trying to get "regular work writing for terribles" (58), and Kurtzberg, a young artist, bring their "'thing'" (58) to Yacov and Itzhak: a story about a man from the future sent back in time, depicted by Kurtzberg as a "muscular figure wearing a skin-tight costume" (58) . . . and, yes, think Superman, for this man from the future will have "the Hebrew letter Shin" (58) as a log on his chest, which stands for "'Shaddai,'" or "'The Almighty'" (58). Initially sceptical, Itzhak sees the potential in what Segal and Kurtzberg have brought to Wonder House, having the flash of inspiration to put the focus on Kurtzberg's illustrations as the main narrative, with Segal's text used in "'snippets'" (59) on top of the illustrations. "'This could work'" (59), Itzhak says, and the reader agrees, because the reader knows he's right. So, a story about the very moment of the creation of a new form and a new genre of story, and thus a story that is also about Story itself. Roberson's shifting of the origins of SF and comics to another planet and into another cultural register from the default Anglo-American roots of both SF and comics in our history lends his piece another layer of inspiration, surprise. (I particularly appreciate his use of SF to imagine the beginnings of SF . . . and the publication of his story in a magazine that can be seen as the modern-day evolution and inheritor of the pulps, er terribles.)

• See Part II.

4. Chris Roberson, "Wonder House" (pg. 53-69) *** 1/2

Read 31 Jan. 2010. Alternate history SF, (re)imagining the confluence of events and inspirations that created the comic book. I will admit that I thoroughly enjoy this sort of story, which meditates on not just the origins of a form/media (comics) but also treats with playful reverence the origins and concerns of its own genre (SF) -- and does succinctly, never swerving from its tone or its subject, moving the story (and the reader) inexorably to the moment of revelation that is a joy because it is understood, anticipated right at the last second before it arrives. On the planet "Fire Star" (54), Yacov Leiber and Itzhak Blumenfeld have been running "Wonder House Publications" (53) for twenty years, their fortunes rising adn falling (or plateauing) by their ability to publish "terribles" (54) -- i.e., pulp magazines -- that readers desire. Roberson brings us into their publishing house and lives at a moment of crisis and the need for change, as Wonder House's fortunes are in decline, Yacov and Itzhak's editing a bit out of step with readers' current tastes. They brainstorm different ideas for new or renewed stories and series, such as "'war title'" (55) or a "'gun-slinger title'" (55) or a "'character title, like Doctor Buckingham'" (55) or "relaunching Celestial Bureaucracy'" (56), but find various reasons why such titles would not work in the present climate for terribles. In the process, Roberson crafts a history of Fire Star's terribles, which clearly mirrors Earth's history of the the pulps (especially from the Gernsback era of the late 1920s on, I think), bringing that history to a point of transition, for what Wonder House needs is something truly new, truly innovative if it will reclaim its "readership" (57) and marketshare. That something truly new is the simultaneous arrival of SF and comics, as Segal, a young writer doggedly trying to get "regular work writing for terribles" (58), and Kurtzberg, a young artist, bring their "'thing'" (58) to Yacov and Itzhak: a story about a man from the future sent back in time, depicted by Kurtzberg as a "muscular figure wearing a skin-tight costume" (58) . . . and, yes, think Superman, for this man from the future will have "the Hebrew letter Shin" (58) as a log on his chest, which stands for "'Shaddai,'" or "'The Almighty'" (58). Initially sceptical, Itzhak sees the potential in what Segal and Kurtzberg have brought to Wonder House, having the flash of inspiration to put the focus on Kurtzberg's illustrations as the main narrative, with Segal's text used in "'snippets'" (59) on top of the illustrations. "'This could work'" (59), Itzhak says, and the reader agrees, because the reader knows he's right. So, a story about the very moment of the creation of a new form and a new genre of story, and thus a story that is also about Story itself. Roberson's shifting of the origins of SF and comics to another planet and into another cultural register from the default Anglo-American roots of both SF and comics in our history lends his piece another layer of inspiration, surprise. (I particularly appreciate his use of SF to imagine the beginnings of SF . . . and the publication of his story in a magazine that can be seen as the modern-day evolution and inheritor of the pulps, er terribles.)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)